Support for a Neurobiological View of Trauma With Implications for Art Therapy

Every bit an art psychotherapist, I am ofttimes asked how working with art tin can facilitate recovery from sexual abuse. This sometimes difficult to explicate in words alone and the confidentiality of the work fabricated in art therapy prohibits the sharing of visual material. In a brave exception to this rule, a client of mine, Maxine*, has given me total permission to share her story. I am indebted to her for allowing me to employ her work to demonstrate how art psychotherapy can aid children and adults heal from the trauma of sexual abuse.

*All names have been changed to preserve anonymity

Sexual abuse and art therapy: a example study

Post-traumatic stress disorder is a response to experiencing or witnessing an overwhelming traumatic upshot, or series of events and has been acknowledged as 1 of the long-term furnishings of kid sexual abuse (Briggs & Joyce, 1997). Maxine was 16 when I began working with her and had a PTSD diagnosis. She had experienced a decade of sexual abuse by her grandfather and trigger-happy a rape at gunpoint by a stranger when she was 8. She was disturbed past flashbacks and nightmares of the abuse, to the bespeak where she was agape to sleep.

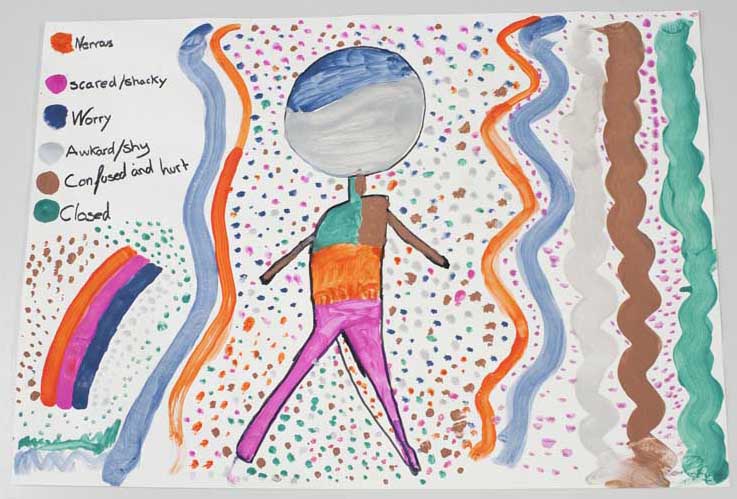

Connecting with the body

In one of her early sessions, I asked Maxine to visually correspond how she felt emotionally on a daily basis. Her artwork allowed me to see a visceral picture of her trauma that would accept been difficult to achieve verbally. The scared and nervous feelings around the legs and stomach signify the triggering of the nervous organisation, what are chosen the 'hyper arousal' symptoms of PTSD: panic, anxiety and being hands scared or startled.

The body map: A2 cartridge newspaper, acrylic and pen

Dissociation

In 'The Black Hole' Maxine expressed a feeling of dissociation. This is a mail-traumatic symptom, which is occurs when a person 'zones out' during a traumatic event in order to cope. It is linked to the evolutionary freeze response (Gantt & Tinnin, 2008). The trauma therapist Babette Rothschild describes dissociation as 'an instinctive response to save the self from suffering' (2000:13).

At the time of the abuse dissociation is an adaptive strategy, which allows the survivor to develop a self that is driveling and a self that can collude with the abuser for survival. When the survivor is no longer exposed to the abusive state of affairs this strategy becomes maladaptive and tin can keep them socially and emotionally isolated, as they dissociate in everyday life. In 'The Blackness Hole' the use of the art media showed me how distant and divide Maxine felt from those effectually her.

The Black Pigsty: A2 acrylic on carbohydrate paper

Reflecting on this painting at the finish of therapy, she said that the large fasten bursting her through the bubble may have reflected her wish to be awoken from the dissociative state. The lack of arms of the people in the image convey a sense of powerlessness and inertia.

Splitting

Splitting of the self is some other dissociative symptom of PTSD, which trauma therapist Judith Herman refers to as the 'abused and exalted self' (1992: 106). Fine art psychotherapy'southward unique advantage is that the art object can contain the duality of the 'dissociative fragments' (van der Kolk, 1987: 184) of a traumatized client. The skilful and bad self (Klein, 1946) can exist expressed simultaneously in an artwork, whereas the bad self can often get carve up off if addressed merely verbally.

'In bed': Coloured pencil on A3 cartridge paper

'In bed' shows a clear demonstration of this phenomenon in Maxine's process. The bad cocky appears modest and helpless below the rain cloud and a mere shadow lying next to the proficient cocky. In the sunshine, the adept self appears strong, more than adult in stature and property a dog that Maxine oft cited as her simply protector. This slice marked a moment in her therapy where Maxine's daytime PTSD flashbacks began to abate equally she realized that she was at present not as helpless every bit she had been at the fourth dimension of the abuse. The defiant effigy on the left or 'skillful self' seems to admit this.

The sense of touch and the brain

Working physically with art materials can take a positive effect on the hyper-arousal symptoms of PTSD. In kid trauma survivors, it was found that past becoming enlightened of different parts of the torso moving during the manipulation of fine art materials (known as kinesthetic activity), released tension, facilitated relaxation and increased ability to tolerate stress (Chapman et al, 2001). A British survey of sexually abused young people plant that the creative fine art process reawakened physical sensations that they had blocked out (Murphy, 1998).

The use of dirt, with its need to be manipulated with the easily tin connect survivors to the haptic sense (the sense of touch on). The sensations from joints and muscles experienced in the manipulation of art materials activate emotions because the amygdala (where we process emotions) connects directly to the primary somatosensory cortex (where we process bodily sensations) and to the occipital lobe (where nosotros process visual data) creating a neurobiological link between impact, visual perception and emotion (Lusebrink, 2004:127).

'A flower'. Clay, modeling wire and acrylic, H21cm ten D16cm

At the outset of my therapeutic relationship with Maxine she produced 'A bloom', a phallic symbol fabricated of clay. Hagood (2000) speaks of the re-enactment of sexual corruption that tin can be stimulated by fluid materials, referencing bodily fluids. The curl pot that surrounds the flower had been made jointly and after its completion Maxine decided to create the blossom part which she told me she 'wanted to stand up'. Being able to utilize the symbol of the flower to represent a penis permitted Maxine to bring her traumatic experience to the therapy room via the art. At the end of her therapy, Maxine reflected that had I interpreted the symbol of the bloom at that betoken in her therapy, she may non accept continued, as it would have been too overwhelming for her. The employ of symbolization in the artwork enabled her to procedure the trauma and bring her experience to the therapy room at a tolerable stride without flooding her with traumatic memory and retraumatizing her.

Narrative edifice with art

Equally trauma memories are so fragmented, there is natural tendency for clients to want to map out their trauma in some fashion to make sense of information technology, connecting visual fragments with linguistic communication. Halfway through a yr of working with Maxine, she spontaneously produced 'The Charm Bracelet'. This was a trauma narrative that charted her abuse throughout her life, the sinister metaphor of the charm bracelet as her life and the incidents of abuse every bit 'charms' given to her by her abusers, added on every twelvemonth.

'The Charm Bracelet.' Felt-tip and pencil on A2 cartridge paper

This slice of work seemed to take a dual purpose, it put Maxine's abuse history and our work together into a context, but it also appeared to lessen her difficulty in naming and feeling emotional states. The work described the corruption in not bad detail, but it was this conscious rendering of PTSD triggers and a timeline of events that contextualized her experience.

It was a unification of explicit retentivity (cognitive, witting, and linguistic communication-based) with implicit retention (emotional, visual and sensory). As the area of the brain responsible for language shuts downwards during traumatic experience (Rausch et al, 1996) traumatic memories are recorded visually. Therefore, connecting both body-based retention, prototype and linguistic communication allows the trauma to processed and converted into autobiographical retentivity, which no longer triggers the amygdala (where fearfulness is processed in the brain). This marked a decrease in Maxine's PTSD hyperarousal symptoms.

Expression of rage and finding resolution

The aroused feelings towards the perpetrator can be physically enacted with the art materials, which tin can help to foreclose the child from turning the acrimony inwards or enacting it in the form of self-harm (Ambridge 2008; Irish potato, 1998). The expression of rage by the sexually abused child is facilitated by the kinesthetic aspects of working with the fine art materials. The expression of anger can lessen depressive symptoms and can be worked towards as a therapeutic goal. If the abuse was perpetrated by a family fellow member, anger often had to exist repressed in order for the kid to survive.

The expression of anger tin be adaptive for a menstruum of time, but if information technology becomes stuck or frozen in repetitive re-enactment it tin can retraumatize the survivor (Herman, 1992; Gil, 2006). Subsequently a long period of establishing the trauma narrative of Maxine's abuse, she announced that she would like to make a model of her rapist.

'The Sacrifice of The Rapist': Clay, wood, acrylic and paper. H16cm x W22.5cm x L29.7cm

The act of stabbing the rapist with sticks in his rima oris and torso seemed to replicate the oral sex acts Maxine had been forced to perform and the painful intrusion in her physically immature torso that penetration had caused her. She described it as a 'sacrifice' and the procedure had a ritualistic feel. Later the artwork was completed she acknowledged that she would never be able to 'get fifty-fifty' with her abuser, just the symbolized revenge marked a modify in her behaviour, where she turned her anger into the 'righteous indignation' (Herman, 1992: 189) that began to permit her to accept her feel. At the end of her therapy, she smashed information technology up and this appeared to provide great catharsis.

References

-

Ambridge, K. (2008) The anger of abused children. In: Liebmann, M. (ed.). Art Therapy and Anger. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. pp.27-41.

-

Briggs, Fifty. & Joyce, P.R. (1997) What determines post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology for survivors of babyhood sexual corruption? Child Abuse & Neglect. 21(half-dozen) pp.575-582.

-

Chapman, L., Morabito, D., Ladakakos, C., Schreier, H. & Knudson, Grand.M. (2001) The effectiveness of art therapy interventions in reducing postal service traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms in pediatric trauma patients. Art Therapy. 18(2) pp.100-104.

-

Gantt, L. & Tinnin, L.Westward. (2008) Support for a neurobiological view of trauma with implications for art therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 36(3) pp.148-153.

-

Gil, E. (2006) Helping Abused and Traumatized Children: Integrating Directive and Nondirective Approaches. New York: Guilford Printing.

-

Hagood, M.M. (2000) The utilise of Art in Counselling Child and Adult Survivors of Sexual Abuse. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

-

Herman, J.L. (1992) Trauma and Recovery: From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror. New York: Basic Books.

-

Klein, M. (1946). 'Notes on some schizoid mechanisms', International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 27 pp.99-110.

-

Lusebrink, 5.B. (2004) Art therapy and the encephalon: An attempt to understand the underlying processes of art expression in therapy. Art Therapy. 21(iii) pp.125-135.

-

Murphy, J. (1998) Art therapy with sexually abused children and young people. International Journal of Fine art Therapy: Inscape. 3(i) pp.10-sixteen.

-

Rausch, S.Fifty., van der Kolk, B. A., Fisler, R.Eastward. & Alpert, N.M. (1996) A symptom provocation study of posttraumatic stress disorder using positron emission tomography and script-driven imagery. Archives of General Psychiatry. 53(5) pp.380-387.

-

Rothschild, B. (2000) The Torso Remembers: The Psychophysiology of Trauma and Trauma Treatment. New York: Norton.

-

van der Kolk, B.A. (1987) Psychological Trauma. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Source: https://www.thepalmeirapractice.org.uk/expertise/2018/2/22/working-with-sexual-abuse-in-art-therapy

0 Response to "Support for a Neurobiological View of Trauma With Implications for Art Therapy"

แสดงความคิดเห็น